Enab Baladi – Bisan Khalaf

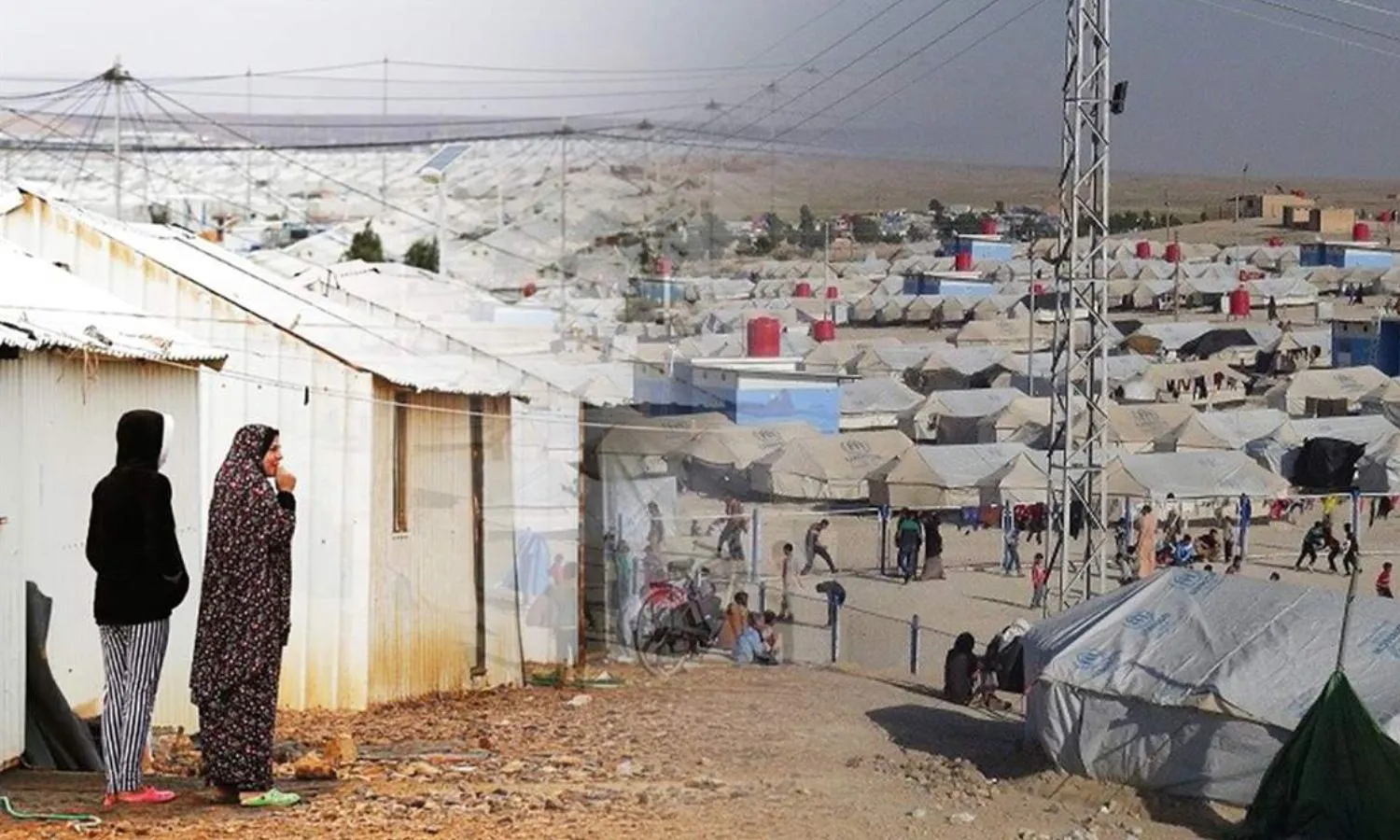

Half a month felt like a nightmare for Israa al-Omr and her family, after the Lebanese authorities gave them 15 days to vacate the “Zahle” camp for Syrian refugees in Lebanon.

The authorities, who decided to dismantle the camps and return their residents to Syria “voluntarily,” did not give Israa’s family—originally from the countryside of Homs—enough time to prepare for the return to Syria, nor any guarantee of what awaited them on the other side of the border.

The “National Litani River Authority” in Lebanon announced the dismantling of parts of the refugee camp in the Zahle–Muallaqa area, after giving residents 15 days to vacate it.

In a statement published by the “Lebanese National News Agency” on June 26, the “National Authority” explained that those in charge of Camp No. 004 in the Zahle–al-Muallaqa area had begun dismantling parts of the camp after the legal deadline had expired.

Pushed into the Unknown

Enab Baladi met Israa and her family in the town of Jdeidet Artouz, where they live with three other families who returned together from the same camp and decided to share one house so they could afford to pay the rent in half-yearly installments.

“It was never a voluntary return. They pushed us into the unknown. We left Syria in 2014; we do not know Syria now—it feels like a new country to us,” Israa told Enab Baladi.

She added that a return to Syria was inevitable, “but it was not coordinated in a way that guaranteed our right to a safe return, or guarantees that ensure our rights and our future in terms of living and housing.”

Israa’s home was bombed and destroyed during the war in Syria. Like other Syrian families, she does not have enough to rebuild the house amid the difficult economic situation, describing it as a “second displacement but inside Syria.”

Second Displacement Without Protection

With Israa’s family lives the family of Khaled al-Hassan (Abu Mustafa) from the town of al-Muadamiyah in the western countryside of Damascus.

“Abu Mustafa” left his job as a carpenter in Lebanon and returned to Syria when the camp was dismantled, only to find his house half destroyed. This forced him to live with families in a home without windows or furniture, with no electricity, and with water only supplied by private tankers for sums the families cannot afford.

He described his return from Lebanon to Syria as “unfair,” akin to a return into the unknown.

“We live on the charity of neighbors or some aid provided by charitable associations. Even bread we sometimes cannot buy,” said Abu Mustafa.”

Sometimes he works with some men from the families living with him to collect plastic from garbage containers.

In a low voice, he said, “We did not return to a homeland; we are fleeing from a country where we lost everything, and we returned to it with nothing—no house, no job, not even a bread card.”

Although a few humanitarian organizations provide aid in Syria, the absence of a comprehensive government plan to absorb returnees, and the lack of a social safety net leave most returnees vulnerable to renewed displacement—but this time inside Syria itself.

Most of the areas to which refugees are returning—especially in the countryside of Homs, Damascus, Daraa, and Hama—still lack basic infrastructure. They have no functioning hospitals, no schools operating at full capacity, and their electricity and water networks are out of service or unstable.

Enab Baladi attempted to contact the Ministry of Social Affairs and Labor to inquire about its plans and projects to secure job opportunities for those returning from camps in Lebanon and to integrate them into society, but had not received a response as of the time of writing this report.

Return Under Political Pressure

Syrian refugees in Lebanon have fallen victim to political pressure exerted on Lebanon to dismantle informal camps, according to George Hanna, a worker with non-profit relief organizations in Lebanon.

Hanna told Enab Baladi that municipalities and security agencies pressure refugees, forcing them to sign pledges to return to Syria. The camps are then dismantled and the refugees deported within days. Aid is cut off immediately, and the journey to Syria is at their own expense.

He noted that the Lebanese security agencies are pursuing a policy of tightening restrictions on Syrians, arresting them if they are found without residency papers, adding, “This restriction is a form of intimidation for those still living in Lebanon to force them to return to Syria.”

Racism against Syrians in Lebanon has intensified with the collapse of the regime in Syria and the start of camp dismantling—another form of pressure to force many to return, a process authorities label “voluntary.”

Community and Institutional Cooperation

Social affairs expert Dr. Rand Rankoussi said that the return of Syrian refugees from Lebanon is taking place in the absence of even the minimum requirements for stability, making it more akin to an “undeclared forced return.”

She added that when a refugee returns to an environment lacking infrastructure and basic services, without security guarantees or reintegration programs, this risks creating a new humanitarian crisis inside Syria itself.

Rankoussi stressed that such returns—often driven by economic hardship or harassment in the host country—“cannot be considered fully voluntary, especially in the absence of alternatives for returnees.”

International and local support for return operations remains almost absent, exacerbating the fragility of returnees and increasing the likelihood of renewed internal displacement, according to Rankoussi.

She believes that the Ministry of Social Affairs and Labor, in cooperation with humanitarian organizations—both international and local—must work on programs to empower and support returnees from refugee camps, possibly involving them in the reconstruction process to create jobs for them and their families.

Despite the major challenges still facing Syria, the negative impact of unorganized returns can be mitigated through the creation of temporary community reception centers run by local volunteers and civil society organizations, to provide psychological and informational support to returnees until official relief efforts are in place, Rankoussi said.

She pointed to partially successful local models in some Syrian villages, where residents cooperated with humanitarian organizations to rehabilitate abandoned schools as temporary shelters or to provide primary care services.

“These initiatives need organized support from the government and donors, but they prove that the local community can play a pivotal role in easing the shock of return,” she added.

She concluded by saying that sustainable solutions begin with the recognition that safe return does not only mean the absence of war and fighting, but also the presence of a supportive environment that preserves dignity and opens doors to hope again.

Plan to Return More Than 200,000 Refugees

The head of the Lebanese ministerial committee tasked with the Syrian refugee file, and Deputy Prime Minister of Lebanon, Tarek Mitri, said that the committee has completed a new plan for the return of refugees, consisting of several stages, and will present it to the Council of Ministers at the earliest opportunity for approval to proceed with it.

He confirmed that the first phase of the return of Syrian refugees from Lebanon to Syria will begin before the start of the school year in early September, noting the difficulty of determining exact numbers, but estimating between 200,000 and 300,000 people, depending on the success of the process.

In a statement to Asharq al-Awsat newspaper on June 8, Mitri said that he takes into account the fact that a large number of Syrians have already begun to return to their country, for various reasons, but there is no exact figure for the number of returnees.

According to a survey conducted by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in Lebanon, Mitri explained that a significant portion of Syrian refugees expressed readiness to return.

Mitri stated that the Syrian government does not oppose the return of refugees, though it is concerned about living and housing conditions. All of this, he said, makes voluntary return possible and gradual.

The return mechanism will be divided into organized and unorganized returns. In the former, names will be registered and buses will be provided to transport refugees to Syria, with each receiving $100.

As for unorganized return, the displaced person will set their departure date and arrange their own transportation, but will also receive $100. Mitri added that the Lebanese General Security will exempt those leaving from fines incurred due to expired residency permits, on the condition that they do not return to Lebanon.

The post Syrians Face “Forced Return” from Lebanon and Displacement in Syria appeared first on Enab Baladi.