The death of Syrian minor Muhannad Mohammed al-Ahmad (14), who had been detained for three months at Lebanon’s al-Warwar juvenile prison, has drawn outrage from rights groups amid conflicting reports over the cause of death.

The medical report issued by al-Warwar prison stated that the boy died on September 29 due to acute cardiac and pulmonary failure. His family, however, insisted he was subjected to “severe torture” that led to his death, while leaks from inside the prison claimed that Muhannad had “committed suicide.”

The victim’s father told the Syrian Detainees News Agency in Lebanon (SDNAL) on Wednesday, October 1, that his son had been living in Beirut for years and was arrested about three months ago “without any contact with the family.”

He added, “My son was previously held for six months when he was even younger, and he never attempted suicide. How can they now claim he killed himself? I have no doubt that Muhannad was killed inside the prison.”

Muhannad’s father expressed regret that this happened in a facility designated for minors, questioning why his son was denied the phone call normally permitted for all prisoners.

Muhannad’s brother, who was initially detained with him before being transferred to Roumieh central prison, confirmed to the Syrian Detainees News Agency in Lebanon that his sibling “was in good health at the time of arrest.” He said they were both subjected to torture and beatings by security forces before being separated, after which all contact with Muhannad was lost until his death was announced.

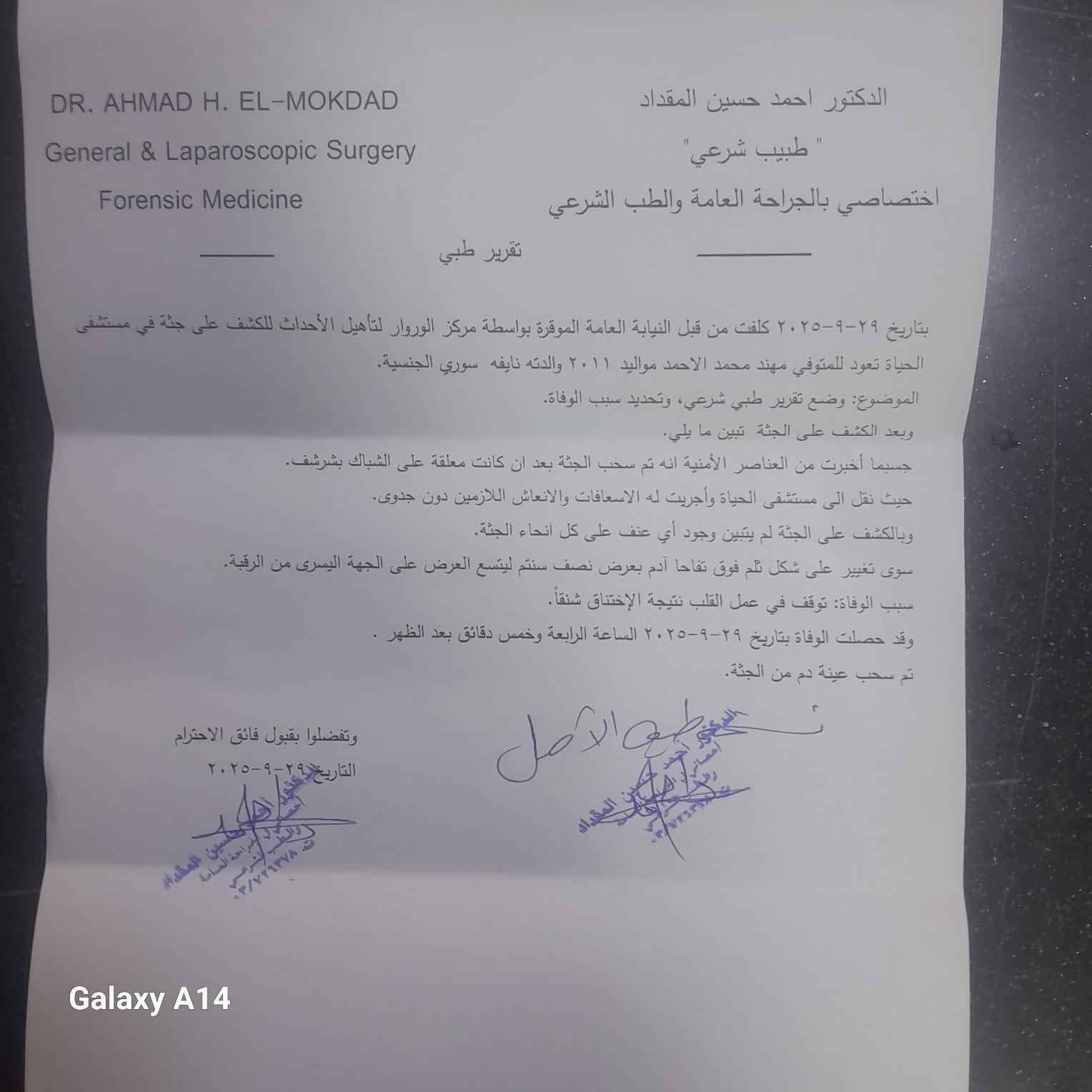

Despite days passing since the incident, Lebanon’s Internal Security Forces have not issued an official statement clarifying the circumstances of the death. An initial medical report, received by a relative of the victim, attributed the cause to “acute cardiac and pulmonary failure,” stating that doctors had attempted resuscitation “but without success,” according to a forensic doctor who examined the body at al-Hayat Hospital in Beirut.

The forensic doctor’s report, a copy of which was obtained by Enab Baladi, denied the presence of any signs of violence on the victim’s body.

Medical report issued by al-Warwar prison outlining the cause of the boy’s death

Family’s Account

Muhannad’s brother, Louay al-Ahmad, who viewed the body, reported seeing “blue bruises on the neck and shoulders, and traces of blood on the corpse.” He considered these signs “inconsistent with a claim of natural death,” refusing to receive the body until it was examined by an independent forensic doctor.

In contrast, SDNAL quoted two security sources saying the minor had “committed suicide in his detention cell,” without disclosing motives or offering further details.

SDNAL describes itself as a media agency specialized in producing journalistic and news content on Syrian detainees in Lebanese prisons, aiming to deliver their voices professionally to the media.

“Deep Gaps” in Juvenile Detention System

Amira Sukkar, head of the Union for the Protection of Juveniles in Lebanon, described the boy’s death as a “human tragedy.”

Speaking to Enab Baladi, Sukkar explained that the minor had been detained for three months, during which he was moved from a juvenile holding cell to the juvenile building at Roumieh prison, before being recently transferred to the newly established al-Warwar facility.

Despite the new building’s modern standards, she noted, “bricks alone are not enough.” She stressed the need for qualified educational, psychological, and social specialists.

Rights Advocacy Outcry

Mohammad Sablouh, director of the Cedar Center for Legal Studies in Lebanon and a rights advocate for migrants, told Enab Baladi that “this incident raises major questions about the conditions of detention and treatment of minors in Lebanese prisons.”

He confirmed that Muhannad had no contact with his family since being arrested on charges of “cable theft,” and that reports indicated he was beaten and tortured, with no psychological support or fair trial.

Sablouh added, “It is inconceivable that a 14-year-old child would commit suicide in a newly built facility that was said to meet international standards. If there was good treatment and psychological care, why would he take his own life?”

Slow Trials and Legal Hurdles

Sukkar pointed to delays in judicial proceedings as a major challenge, saying that minors may wait months for a hearing due to logistical issues, absent parties, or the lack of legal representation.

She added that some judges refuse to appoint a lawyer for a minor if the parents are absent, which prolongs detention and worsens legal and psychological suffering.

Sablouh, meanwhile, held al-Warwar prison administration directly responsible for the death, criticizing the Interior Ministry for failing to issue any official statement 48 hours after the incident.

He confirmed that he would represent the victim’s family in filing a lawsuit against the prison administration and to hold those responsible for violations accountable.

“The judiciary in Lebanon is negligent, if not at times conscienceless,” he said, accusing it of turning a blind eye to torture in prisons under the pretext of blackmail or politicization.

|

“We were the ones who leaked the news of the Syrian minor’s death, and so far no official clarification has been issued by the concerned authorities. We did not accept the initial forensic medical report and requested a second one at the family’s demand.” Mohammad Sablouh

|

Mental and Social Care Crisis

Amira Sukkar, head of the Union for the Protection of Juveniles in Lebanon, confirmed that all minors held at al-Warwar prison suffer from severe psychological distress due to prolonged detention, uncertainty about their trials, and not knowing how long they will remain incarcerated.

She relayed that the prison’s social delegate had noted the deceased minor’s poor mental state and referred him to a hospital on September 9, where he was prescribed treatment. However, the absence of daily follow-up by a licensed prison psychologist prevented his condition from improving.

“These children ask painful questions every day: How long will I stay in prison? Why can’t I see my family? When will I get out?” Sukkar said, adding that such confusion is part of their daily suffering.

Challenges and Urgent Needs

Sukkar explained that social delegates regularly visit the facility and coordinate with judges to expedite cases, including replacing custodial measures with alternatives. While she highlighted “success stories” in this regard, she also criticized the denial of family visits for minors, despite an official memorandum from the Public Prosecutor permitting them.

She listed the most pressing challenges, stressing the need to:

-

Separate minors’ files from those of adults to avoid delaying hearings.

-

Hire three additional social workers to follow cases more closely.

-

Appoint a licensed psychologist inside the prison for daily support.

-

Speed up judicial hearings.

-

Monitor minors’ conditions with their families and encourage parents to accept, rather than abandon, their children.

“What happened with the minor at al-Warwar reminds us that we may lose young, tormented lives behind walls, scarred by social stigma and family abandonment,” Sukkar said.

She concluded that both the system and society must free themselves from their constraints and “embrace with awareness and open hearts the dignity of these children who have lost trust in love, safety, law, and justice.”

Culture of Torture and Neglect

Mohammad Sablouh, director of the Cedar Center for Legal Studies in Lebanon, spoke of a “deeply entrenched culture among Lebanese security agencies in dealing with detainees, particularly minors, as enemies of society rather than children in need of rehabilitation.”

“The minor is deprived of basic rights, including contact with his family or psychological support. When he is subjected to torture and ill-treatment, it becomes almost natural that he would think of suicide,” he said.

Sablouh reminded that Lebanon has a Juvenile Protection Law setting out basic standards for dealing with minors, but the reality is “completely different.”

“Instead of prisons being centers for reform and rehabilitation, they have become places that produce criminals, where detainees are seen as numbers rather than human beings who need care, food, and rehabilitation,” he added.

Call for Urgent Action

Sablouh urged the Minister of Interior and the Minister of Justice to visit prisons and spend a night inside to witness firsthand how inmates are treated, warning of a potential social explosion if such conditions persist.

He criticized the concealment of deaths under claims of cardiac or pulmonary arrest, saying this is no longer acceptable.

“What happened to Muhannad al-Ahmad requires a transparent investigation and accountability before the tragedy repeats itself,” Sablouh said.

This incident adds to a series of previous deaths of Syrian detainees in Lebanese prisons attributed by rights groups to “medical neglect, torture, suicide, or unclear causes.”

Rights estimates suggest there are around 2,000 Syrians detained in Lebanon, with more than 80% held without trial, under conditions described by Arab and international reports as “inhumane.”

The post Death of Syrian minor in Lebanese prison sparks conflicting accounts appeared first on Enab Baladi.