Enab Baladi – Mohammad Kakhi

The revolutionaries who entered Damascus wasted little time before beginning to reorganise and restructure Syria’s domestic policies. After the “Military Operations Administration” secured the capital and protected public property, it announced that the new government would begin its work as soon as it was formed.

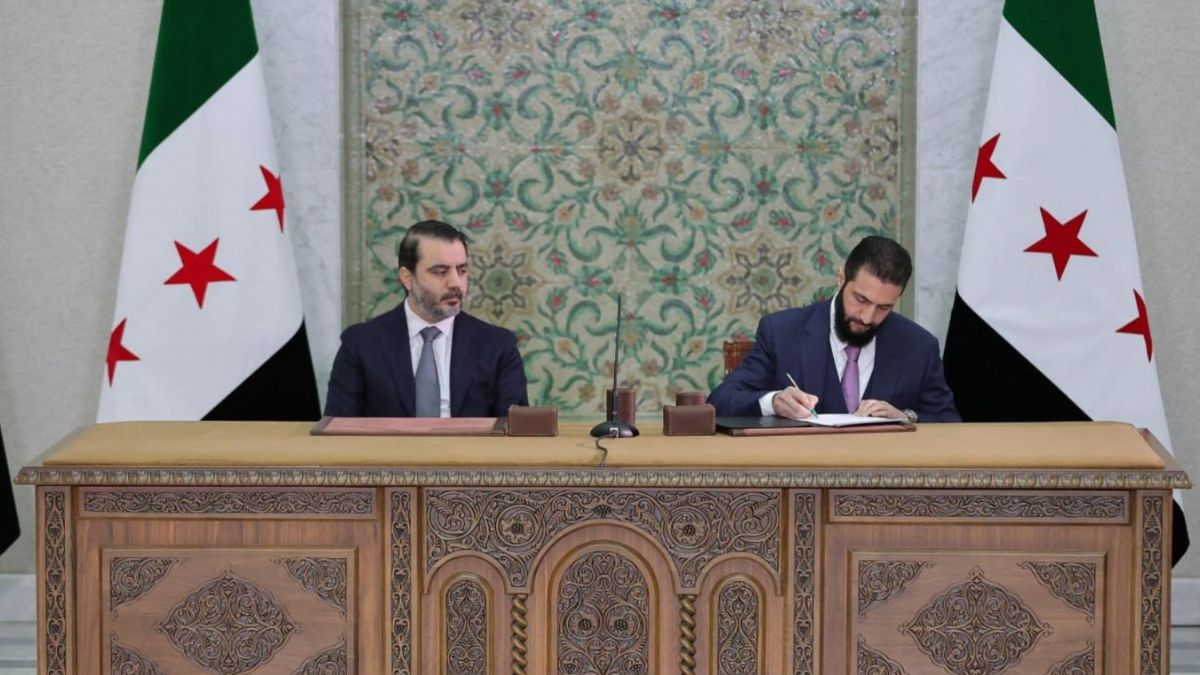

While news of the ousted Assad’s escape dominated TV screens, the country was being rushed into the operating room in one go. On 9 December 2024, the “Salvation Government”, which had previously operated in Idlib in northwestern Syria, held a session with officials from the former Syrian regime’s government to transfer institutions and hand over files from the latter to the new government.

After that, on 10 December 2024, the “General Command” in Syria tasked Mohammed al-Bashir with heading a caretaker government until 1 March 2025.

On 30 March, Syria’s transitional president, Ahmed al-Sharaa, announced the formation of the new Syrian transitional government. In the ceremony held to unveil the cabinet, President al-Sharaa said Syria was witnessing the birth of a new phase in its national journey, and that “the country faces major challenges that require us to stand united and cohesive.”

In his first cabinet meeting with the ministers of the new transitional government, on 8 April, al-Sharaa outlined the government’s priorities and the responsibilities of its various ministries. He emphasised the importance of the reconstruction agenda, the need for strategic urban planning in cities and towns, the civilisational and cultural links of the built environment, the primacy of the Syrian citizen, and repairing the devastation inflicted by the previous regime on state structures, particularly in economic and financial systems.

Building the state must be done with a state mindset, not with a revolutionary or armed factions mindset.

Ahmed al-Sharaa

Syria’s transitional president

Victory Conference, starting from the People’s Palace

Forces of the “Military Operations Administration” reached Damascus on 8 December 2024, after an 11-day battle that began in western rural Aleppo and ended in Homs. The ousted Syrian president, Bashar al-Assad, fled to the Russian base in Latakia on the Syrian coast and from there to Moscow.

On 29 January, opposition armed factions convened at the People’s Palace in Damascus and declared from there the victory of the Syrian revolution and 8 December of each year a national holiday. They appointed Ahmed al-Sharaa as Syria’s president for the transitional period, authorised him to form an interim legislative council, dissolved the Baath Party and the National Progressive Front parties and banned their reformation, dissolved the security services and the army, called for the creation of a new security institution and the building of a new army on national foundations, dissolved the People’s Assembly, repealed the 2012 Constitution, and dissolved all military factions, as well as revolutionary, political, and civil bodies, merging them into state institutions.

Factions that participated in the Victory Conference:

- Hayat Tahrir al-Sham

- Ahrar al-Sham Movement

- Jaysh al-Izza

- Jaysh al-Nasr

- Ansar al-Tawhid

- Faylaq al-Sham

- Joint Force

- Jaysh al-Ahrar

- Jaysh al-Islam

- Free Syrian Army

- Nour al-Din al-Zenki Movement

- al-Jabha al-Shamiya (Levant Front)

- Harakat al-Tahrir wal-Binaa (Liberation and Construction Movement)

- Sultan Murad Division

Absent from the conference were the commander of the “Eighth Brigade”, Ahmad al-Awda, who sent representatives on his behalf, and all faction leaders in Suwayda (southern Syria). A source from Suwayda told the Lebanese website “al-Modon” at the time that all commanders, including leaders of Bedouin tribal factions, collectively boycotted the conference in protest at the way they had been invited.

The website reported that only one faction, which it did not name, received an official invitation directly from the conference organisers and then took it upon itself to distribute invitations to the others, which caused widespread resentment among them, as it was seen as a mere “token invitation”.

“There were varying positions,” the source said. “Some factions wanted to attend, while others objected to the form and manner of the invitation and to not knowing the conference agenda or their role in it.” Their absence, therefore, should not be seen as hostility or a sign that they had entered into a conflict with al-Sharaa.

National Dialogue Conference, SDF absent

The Syrian National Dialogue Conference began its work on 24 February in Damascus, with more than 600 participants from different governorates, in what was described as a political milestone that would serve as an “initial test of the seriousness of the transitional phase”.

Participants held six workshops on transitional justice, constitutional design, institutional reform, public freedoms, the role of civil society, and economic principles.

Although the Preparatory Committee stressed that the conference was the culmination of more than 30 meetings it had held in the governorates, drawing on around 4,000 participants and nearly 2,200 written submissions, the process faced sharp criticism over the invitation mechanism, the absence of clear criteria for representation, and the fact that invitations arrived less than 48 hours before the opening, prompting political and academic figures to decline to attend.

During the preparatory sessions preceding the conference, complaints arose about the chaotic management of discussions and disregard for the agenda. The committee maintained that the final recommendations would form the basis for a provisional constitutional declaration and institutional reform plans.

With insufficient time to debate core issues, organisers hoped the conference would serve as an “entry point” to draft a new social contract. Its critics, however, see it as a symbolic step that falls short of the deep requirements relating to the relationship between central authority and local forces, the future of governance in the east and south, and the form of the coming constitutional system.

Both the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and the Democratic Union Party (PYD) were absent from the conference, amid mutual recriminations between the Preparatory Committee and political forces in northeastern Syria. Hassan al-Daghim, spokesperson for the Preparatory Committee, said at a press conference attended by Enab Baladi on 13 February that the SDF does not represent the Kurds and would not be invited to the conference, insisting that “no one possesses an exclusive or sequestered share of the homeland” and that participation would be limited to those “who lay down their arms and integrate into state institutions”.

For its part, the PYD leadership refused to recognise the conference or its outcomes. Salih Muslim, a member of the party’s presidential council, said the conference “does not represent the mosaic of Syrian society” and that northeastern Syria is “not bound to implement its decisions”, arguing that excluding the institutions of the Autonomous Administration and the Syrian Democratic Council (SDC) was an attempt to sideline the components that control the region.

Key outcomes of the National Dialogue Conference included:

- Preserving the unity of the Syrian Arab Republic and rejecting partition.

- Condemning Israeli incursions into Syrian territory and calling for an immediate, unconditional withdrawal.

- Restricting arms to the state and building a professional national army.

- Expediting a provisional constitutional declaration suited to the requirements of the transitional phase.

- Accelerating the formation of an interim legislative council to assume legislative authority based on the criteria of competence and fair representation.

- Establishing a constitutional committee to draft a proposed permanent constitution for the country.

- Elevating freedom as a supreme value in society.

- Respecting human rights, supporting women’s participation in all fields, protecting the rights of the child, ensuring support for persons with disabilities, and activating the role of youth in the state and society.

- Entrenching the principle of citizenship and rejecting all forms of discrimination based on ethnicity, religion, or sect, while ensuring equal opportunities away from ethnic and religious quota systems.

- Achieving transitional justice by holding accountable those responsible for crimes and violations, reforming the judicial system, and enacting the necessary legislation and mechanisms to guarantee justice and restore rights.

- Consolidating peaceful coexistence among all components of the Syrian people, and rejecting all forms of violence, incitement, and revenge in a way that reinforces societal stability and civil peace.

- Reforming and restructuring public institutions, launching digital transformation, and revisiting recruitment criteria based on patriotism, integrity, and competence.

- Ensuring the participation of civil society organisations in supporting society.

- Developing the education system and reforming curricula, with plans to close learning gaps, guarantee quality education, and invest in vocational education to create new job opportunities.

Religious leaders shake hands with Syria’s transitional president, Ahmed al-Sharaa, 25 February 2025 (Syrian National Dialogue Conference)

Constitutional declaration, a new legislative era

On 13 March this year, Syrian President Ahmed al-Sharaa received the final draft of the constitutional declaration from the committee of experts formed at the beginning of the month, signed it, and announced the start of a new constitutional process that he said aims to “replace ignorance with knowledge and torment with mercy”.

Over two weeks of discussions, the committee, made up of seven Syrian academics and legal experts, relied on the outcomes of the National Dialogue Conference and on the country’s “constitutional tradition” to produce a draft consisting of four chapters that outline the features of governance during the five-year transitional period. It establishes a strict separation of powers, abolishes the post of prime minister, grants full legislative authority to the People’s Assembly, and vests executive authority in the president.

The committee explained that the declaration contains guarantees for rights and freedoms, affirms the independence of the judiciary, abolishes exceptional courts, and creates a High Elections Commission and another body for constitutional review. It also includes provisions that reinforce the unity of the country, safeguard property and women’s rights, restrict weapons to the state, and define the army’s role as “protecting the homeland and the citizen”.

The constitutional declaration also includes an article that criminalises the glorification of the defunct Assad regime and its symbols, and considers denying its crimes, praising them, justifying them, or downplaying them to be offences punishable by law.

Syrian transitional president Ahmed al-Sharaa signs the draft constitutional declaration, 13 March 2025 (SANA)

“Hybrid” elections for the People’s Assembly

At the Victory Conference in Damascus, faction leaders mandated President Ahmed al-Sharaa to form an interim legislative council. However, Article 24 of the constitutional declaration he ratified on 13 March introduced a different mechanism, providing for a committee to elect members of the People’s Assembly, with the president appointing only one third of the members, an arrangement known in legal terms as a “hybrid mechanism” that combines appointment and indirect election.

Such a mechanism is usually adopted in highly complex environments by blending appointment with sectoral, regional, and political or societal representation. Legal researcher Nawras al-Abdullah, from the Syrian Dialogue Center, sees it as a realistic approach, especially in the first months of the transitional phase, given the exceptional role required of the People’s Assembly at this stage. That role, he argues, is more about driving a legal revolution that responds to changes on the ground than about traditional political work.

After the formation of the High Committee for People’s Assembly Elections on 13 June, the committee issued the interim electoral system for the People’s Assembly on 20 August, following its ratification by President Ahmed al-Sharaa. The system created legal committees, appeals committees, and subcommittees tasked with organising and supervising the electoral process under the umbrella of the High Committee.

According to the electoral system issued by the High Committee, a subcommittee was formed in each electoral district in the provinces. These subcommittees, after consulting with local communities and official local actors, appoint the electoral body, which in turn elects the members of the People’s Assembly from among its members.

The number of members of the electoral body in each district is calculated by multiplying the number of seats allocated to that district by 50. For example, Aleppo province has 32 seats, so the electoral body in the province has 1,600 members.

Candidates for the People’s Assembly must meet several conditions, the most important of which are that they “must not have supported the defunct regime or terrorist organisations in any way, and must not call for secession, partition, or reliance on foreign powers”.

On 6 September, the High Committee for People’s Assembly Elections issued Resolution No. 66, announcing the preliminary results of the Assembly elections for all Syrian provinces.

The results revealed weak female representation, with women making up around 14% of candidates and only 4% of those elected. Rabbi Henry Hamra also ran, becoming the first Syrian Jew to seek office in Syria since former president Hafez al-Assad imposed restrictions on the country’s Jewish community in 1967, but he ultimately failed to win a seat for Damascus province.

The voting process to choose members of the People’s Assembly in Syria by electoral body members begins at the National Library in Damascus, 5 October 2025 (Enab Baladi, Ahmed Muslimani)

“Building genuine bridges” with the public

Anas al-Abdeh, a member of the High Committee for People’s Assembly Elections, said that around 800 laws currently in force in Syria place heavy burdens on citizens and ministries and need to be reviewed for amendment or repeal.

In an interview with the state run Syrian al-Ikhbariya TV channel on 1 November, al-Abdeh added that laws and legislation are passed by simple majority or by a two thirds majority when required, noting that the Assembly will work on approving laws that improve services and ease the burden on citizens.

Nour Jandali, a member of the People’s Assembly, told Enab Baladi that the Assembly’s first task after members are sworn in will be to draft a modern, transparent internal bylaw to regulate the Assembly’s work, define committee powers, strengthen oversight, and entrench the independence of the legislative institution.

The Assembly will then, Jandali said, set priorities for the most urgent laws within the committees that handle them, whether economic, social, or related to governance and reform, and will begin drafting them in a systematic way that meets citizens’ needs.

Jandali considers that one of the key pillars of the current phase is building “genuine bridges” between the people and the Assembly through regular meetings and by opening the Assembly’s doors to citizens’ views and demands.

How does parliament oversee the executive?

Experts interviewed by Enab Baladi say the scope of action available to the People’s Assembly during the transitional period is tightly constrained by the 2025 constitutional declaration and by the nature of the presidential system currently in place.

Dr Ahmad Korabi, a public law professor and member of the committee that drafted the constitutional declaration, told Enab Baladi that any discussion of parliamentary oversight and its limits must begin with the constitutional framework.

“We are currently under a presidential system with a rigid separation of powers,” he said. “This means that the legislative authority cannot intervene in the work of the executive authority, and the executive authority cannot intervene in the work of the legislative authority. The first framework that defines the existence of separation between the two powers is therefore a legal and constitutional one.”

Legal and political researcher Firas Haj Yheia noted that while the Assembly enjoys the power to legislate, it is bound to align any law with the principles governing the transitional period, such as transitional justice and the strict separation of powers. This means its legislative function is “constrained” by the task of rebuilding the state rather than reproducing past patterns of rule.

Haj Yheia also sees parliamentary oversight as conditional, exercised within a framework of “cooperative oversight” that avoids confrontation with the executive authority, given that the current phase is about consolidating stability and building institutions, not paralysing them.

According to Dr Ahmad Korabi, low “political cost” oversight tools can be relied on, such as hearings, receiving complaints, issuing statements, and forming investigative committees, without resorting to higher-level measures such as censure or political accountability.

For his part, legal researcher Nawras al-Abdullah stresses that oversight remains an inherent right of the Assembly even under a presidential system, but that its scope is limited by the absence of instruments such as the vote of no confidence. Instead, he says, the Assembly can use parliamentary investigation and legislation itself as tools of oversight, even if these are not spelled out explicitly in the constitutional declaration.

“All tools that do not entail political or legal liability can be used by the legislative authority to exercise its oversight over the executive authority. I am not talking about a vote of no confidence, nor about questioning in its political sense, nor about accusation and trial. I am talking about tools whose upper limit is a parliamentary investigation committee, and below that hearings, questions, complaints, proposals, and statements. All of these are tools the legislative authority can employ as it monitors the executive authority.”

Ahmad Korabi

Public law professor and member of the constitutional declaration drafting committee

Parliament’s role after its completion

The next People’s Assembly is facing one of the “most sensitive moments” in Syria’s political history, as it is expected to perform a role that goes beyond its traditional constitutional duties and become a pillar of political transition and the construction of new legitimacy, after decades in which parliamentary life was disabled and the legislature reduced to a rubber stamp, experts say.

Legal and political researcher Firas Haj Yahya believes that the Assembly is required above all to enact “transitional phase legislation”, which forms the backbone of the political transformation process. This includes laws on transitional justice, political disqualification, natural resource management, the regulation of party and media work, and the reform of the local security sector. These laws, he says, must be drafted in line with the constitutional declaration and human rights principles, as they will define the shape of the new state and the limits of its authorities.

On the oversight level, Haj Yahya speaks of the need for the Assembly to exercise institutional and transparent oversight over the government’s work and to follow up on its plans on reconstruction, fighting corruption, and economic policy. Oversight must be “effective and not merely symbolic”, he says, and must entrench the principle that no one is above accountability, restoring the parliament’s status as a power in its own right.

The Assembly is also expected to be a partner in launching the constitutional debate, as provided for in the constitutional declaration, through specialised committees and broad societal dialogues that can bring an end to the phase of revolutionary legitimacy and open the way to stable constitutional legitimacy. Added to this is a representative role that is supposed to rise above the language of power and reflect the voices of marginalised and affected groups, such as persons with disabilities, families of victims, displaced people, and residents of conflict affected areas.

Nawras al-Abdullah, from the Syrian Dialogue Center, describes the volume of tasks assigned to the Assembly as “enormous”. He believes the institution is returning today to restore the “threefold balance of powers” after having been absent for decades, and that its legislative effort will be the main determinant of how well Syria can adapt to expected changes. Foreign relations and international agreements will also require the Assembly’s approval, placing it in a position to “shape how the state relates to the world”.

Al-Abdullah believes that the Assembly’s first steps, and the public image it builds in society, will be decisive in determining whether it succeeds or fails in the coming years.

Public law professor Ahmad Korabi considers the Assembly’s first mission to be “restoring trust” and changing the inherited public perception of the legislature as a “clapping chamber” controlled by the security services. He stresses that the Assembly must represent the popular will, not the interests of the executive, and must demonstrate from the outset that it is an elected institution that speaks for citizens.

According to Korabi, the Assembly needs an approach based on “complementarity without subordination” in its relationship with the executive, similar to what South Africa experienced after the fall of the apartheid regime. There, the government was given the power to propose laws to speed up the response to national priorities, while parliament remained independent in oversight and amendment. Syria’s current economic, security, and political situation, he argues, requires a similar approach based on cooperation in sovereign files such as dealing with Israel or confronting separatist tendencies, while preserving parliamentary independence on contentious issues.

The 10 March agreement, a solution awaiting implementation

On 10 March, Syrian President Ahmed al-Sharaa reached an agreement with the commander of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), Mazloum Abdi, providing for the integration of the SDF into Syrian state institutions.

Under the agreement, the rights of all Syrians to representation and participation in political life and in all state institutions are guaranteed on the basis of competence, regardless of religious or ethnic background.

According to its provisions, the Kurdish community is recognised as an integral component of the Syrian state, and the state guarantees its citizenship and constitutional rights.

The two sides agreed to a ceasefire across all Syrian territory, and to the integration of civilian and military institutions in northeastern Syria into the Syrian state administration, including border crossings and oil and gas fields.

President al-Sharaa and Mazloum Abdi also agreed to guarantee the return of all displaced Syrians to their towns and villages and to ensure their protection by the Syrian state, as well as to support the Syrian state in combating remnants of the former regime and all threats to its security and unity.

However, the two parties have disagreed over how to implement the agreement’s provisions, particularly those concerning the integration of SDF military and security forces into Syria’s security and military institutions. Both sides have traded accusations of delay and obstruction. In an interview with the Saudi magazine Al Majalla on 20 November, Syrian Foreign Minister Asaad al-Shibani said the government had “offered everything” to the SDF to facilitate the agreement. In a separate interview with the Mezopotamya news agency on 23 November, Mazloum Abdi said the positive understandings reached in the negotiations were not being implemented on the ground.

Deliberate slowdown

Implementation of the 10 March agreement continues to move slowly, months after it was signed and despite a series of meetings that have involved regional and international mediators. While preliminary understandings have been reached on the military track, including turning the SDF into three divisions and brigades formally linked to the Syrian army and integrating SDF security bodies into the Interior Ministry, these steps are, according to Tariq Hemo, a researcher at the Kurdish Center for Studies, the least problematic aspects of the negotiations.

The core dispute, Hemo told Enab Baladi, lies in issues of a political and constitutional nature, foremost among them constitutional recognition of Kurds in Syria, the drafting of a clear decentralised governance model, and addressing the situation of areas such as Afrin and Ras al-Ain (northeastern Syria), which have seen wide demographic changes. These points, he says, are what block real progress, as they relate to the nature of the state and to the SDF’s future participation in power, not only to rearranging military structures.

Researcher Ayman Dasouki offers a different angle on the causes of delay, arguing that the agreement itself has not gone beyond the level of a general “framework”, with a fundamental difference in how each party interprets its purpose. While the SDF sees the agreement as its gateway to political participation in power, the government views it as a path to reasserting state sovereignty over the entire Syrian territory. This is accompanied, Dasouki notes, by strong sensitivities within the social bases of both parties regarding any concessions, making every negotiating step subject to delicate internal calculations, in addition to the role of regional positions in pushing or obstructing the process.

Anas Shawakh, a researcher at the Jusoor Center for Studies, links the slowdown to two main factors: first, the SDF’s lack of desire to implement provisions that could dismantle the military, security, and civilian network it has built over more than a decade; and second, its inability to implement other provisions because local leadership does not control all centres of power, given the influence of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) over decision making within the SDF.

On the other side, Shawakh notes that the Syrian government did take some practical steps in the early stages of the agreement, such as facilitating movement and civil activities. Yet some of the SDF’s demands are almost impossible to meet, he argues, as they relate to changing the name of the state and the nature of the political system, matters of constitutional design that lie outside the current government’s powers during the transitional phase. This makes such demands closer to a way of buying time or derailing the agreement without saying so openly, in Shawakh’s view.

Signing of the agreement between Ahmed al-Sharaa and Mazloum Abdi to integrate the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) into Syrian state institutions, 10 March 2025 (Presidency of the Syrian Arab Republic)

America tightens the screws on its “spoiled child”

Anas Shawakh, a researcher at the Jusoor Center for Studies, believes that the latest developments, culminating in Syria’s accession to the Global Coalition, reflect a clear escalation in US pressure on the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). He expects this pressure to increase in the coming period, whether through public positions or through undisclosed direct contacts between Washington and SDF leadership. Shawakh does not rule out the US taking steps on the ground to reinforce this pressure, such as withdrawing from certain sensitive points or bases, for example those in al-Hasakah (northeastern Syria).

Shawakh places these developments in the context of Washington’s relationship with both Ankara and Damascus, arguing that the United States is the main guarantor of last year’s ceasefire between the three parties, Turkey, the Syrian government, and the SDF. Washington now seems inclined, he says, to intensify pressure on any party that drags its feet over implementing the 10 March agreement, with most of that pressure likely to be directed at the SDF itself for the structural and political reasons previously outlined.

By contrast, Tariq Hemo, a researcher at the Kurdish Center for Studies, views the Syrian government’s accession to the Global Coalition as a step with important implications, but one that still hinges on a “seriousness test” by coalition states. In Hemo’s view, the coalition will not shift its relations toward Damascus without first being sure of the government’s ability to wage a real fight against the Islamic State group and factions designated as terrorist organisations, such as Hurras al-Din and Ansar al-Sunna.

Hemo believes that Damascus joining the coalition could open the door to closer ties between the government and the SDF, since both would operate under the same international umbrella. Yet this scenario, he cautions, is contingent on the government’s compliance with strict standards and on credible behaviour in counterterrorism. Only then might it be allowed to benefit from the SDF’s extensive experience in this field.

Even so, Hemo stresses that it is too early to speak of the government becoming a genuine partner that the coalition can rely on, or of sidelining the SDF, which has accumulated a substantial record of experience and on-the-ground cooperation that cannot simply be discarded overnight in favour of an actor that has yet to prove its capacity or intentions and that remains surrounded by doubts stemming from the factional nature of its structure.

The Suwayda “roadmap”, no solution yet

The events in Suwayda province (southern Syria) began on 12 July last year with reciprocal kidnappings between residents of the al-Maqous neighbourhood in Suwayda city, which has a majority Bedouin population, and members of the Druze community. The situation then escalated into armed clashes.

The Syrian government intervened on 14 July to end the conflict, but its intervention was accompanied by violations against Druze civilians, prompting local factions to respond, including groups that had been cooperating with the Defence and Interior Ministries.

On 16 July, government forces withdrew from Suwayda after being subjected to heavy Israeli strikes. This was followed by violations and acts of revenge targeting Bedouin residents of the province at the hands of Druze factions, prompting convoys of “tribal mobilisation” to move in their support. The situation later escalated into violations against Druze civilians and Bedouin civilians alike in Suwayda, with the Syrian Network for Human Rights documenting the killing of at least 1,013 people in the province in July alone. The violence also left at least 986 people injured with varying degrees of severity across all sides.

Later, on 16 September, Syria’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Expatriates announced that a roadmap had been agreed to resolve the crisis in Suwayda province, following a trilateral meeting in Damascus that brought together Syrian Foreign Minister Asaad al-Shibani, his Jordanian counterpart Ayman Safadi, and US Special Envoy for Syria Thomas Barrack.

The meeting came as a continuation of previous talks hosted by the Jordanian capital, Amman, aimed at consolidating the ceasefire in Suwayda and finding solutions to the tensions the province has experienced in recent months.

According to a statement by the Syrian Foreign Ministry published on its Facebook page, the participants endorsed a roadmap affirming that Suwayda is an integral part of Syria and that its people are equal citizens in rights and duties. They stressed that closing the trust gap between the government and the population requires gradual steps to rebuild confidence and reintegrate the province fully into state institutions.

A member of the Syrian security forces near the entrance to the city of Suwayda, 15 July 2025 (AFP)

An agreement with Israel as the beginning of a solution in Suwayda

Israel, for its part, is trying to keep the “Suwayda card” in play. According to a Reuters report on 26 September, efforts to reach a security agreement between Syria and Israel “hit a last minute snag” over an Israeli demand to open a “humanitarian corridor” to Suwayda province in southern Syria.

The agency, citing four sources familiar with the talks, said the deal had faltered over Israel’s renewed demand for a humanitarian corridor from Israel to Suwayda.

Israeli ministers repeatedly declare that they will protect the Druze in Suwayda and that they are always prepared to intervene on their behalf in Syria.

Political analyst Mohammad Hamadeh believes that the United States, particularly the administration of President Donald Trump, will intervene, as it has in the past, to impose an agreement between Syria and Israel “at any cost”, based on a US conviction that this file must be resolved in the coming period given what he describes as the “regional and international need for stability” in the region.

Hamadeh argues that the repercussions of any such agreement would be felt clearly in Suwayda. He considers that what is happening there rests on an “Israeli cover” and that once this cover falls the issue will be shelved, as many previous files have been, as soon as international alignments shift.

Speaking to Enab Baladi, Hamadeh said that what is known as the “National Guard” in Suwayda “feeds off the continuation of the Syrian Israeli conflict”. The group, he said, lacks an internal vision or understanding of regional dynamics. In the next phase, he expects a restructuring of the security system in Suwayda through local forces from the province itself, alongside figures such as Suleiman Abdul Baqi and Sheikh Laith al-Balous, with the participation of families and national leaders for whom Damascus remains the main reference point, in managing security and dismantling the networks of kidnapping, smuggling, and drug trafficking that have thrived amid the chaos of recent years.

Local forces that “live off” chaos

Nawar Shaban, a researcher at the Arab Center for Contemporary Syrian Studies, told Enab Baladi that the local forces that have hijacked decision making in Suwayda operate according to a strategy of “keeping things as they are”, neither allowing the situation to collapse completely nor allowing a pathway to succeed that would strip them of the power they have accumulated.

Shaban believes there is international acceptance of the roadmap drafted in Amman, and that the problem does not lie in Suwayda residents rejecting the roadmap or the proposed solution as such. Rather, he says, the problem lies in the presence of “militia forces” that impose their control over the province and block any real shift toward stability. Many national figures in Suwayda sincerely want to move to a better situation, he notes, but run up against a reality in which armed groups control movement, restrict people’s lives, and even limit travel to Damascus without “convincing justification”.

These groups, Shaban argues, benefit from keeping the situation unstable, as this ensures the continuation of their influence, which is built on arms and drug trafficking networks and on protecting cadres linked to former security agencies or to external actors.

The post Syria puts its house in order appeared first on Enab Baladi.